Is obesity a disease?

The WHO calls obesity a disease. The NHS says it's a 'health concern'. Which is right? Let's look at the facts.

If a person has obesity, it means they have excessive body fat – to the point that it threatens the person's health.

These threats are many. Living with obesity puts you at greater risk of developing heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, liver disease, breathing problems and certain forms of cancer.

More than a quarter of adults in England are living with obesity.

But the problem isn't just an England problem. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), one in eight people worldwide live with obesity – and adult obesity rates have more than doubled since 1990.

The WHO has gone so far as to call obesity 'an escalating global epidemic'. If we fail to take action, it warns, 'millions will suffer from an array of serious health disorders'.

Let's take a moment to take that all in.

Obesity can cause serious health problems. It affects millions of people in England and around a billion globally. And the WHO – the leading international health organisation – describes it using the kind of grievous, urgent language usually reserved for global pandemics like COVID-19.

Obesity sounds very much like a disease, doesn't it?

But is it a disease?

Well, that depends on who you ask. Pun intended.

The WHO, you see, is unequivocal in its classification of obesity. Right there on its obesity factsheet – translated into five languages for all the world to read – it says, 'obesity is a chronic complex disease'.

But not everyone agrees – including the NHS.

Is obesity considered a disease in the UK?

If you read the NHS webpage on obesity, you might notice something unusual.

The facts are all sound. The text is helpful, comprehensive and easy to understand. But nowhere in its 1,300-odd words does it describe obesity as a 'disease'.

You might argue that it goes to some lengths to avoid using the term. Obesity is, it says, 'a serious health concern'. It's a 'complex issue with many causes'. And it's 'an increasingly common problem' that 'can cause a number of further problems'.

Obesity is a concern, an issue and a problem. But it's not, as far as the NHS is concerned, a disease.

The NHS isn't alone in taking this stance. However, it does put the NHS at odds with several internationally respected organisations, including the WHO and the European Parliament.

Why don't some organisations consider obesity a disease?

Nobody quite agrees on what a disease is

Part of the problem is that the word 'disease' itself is hard to define.

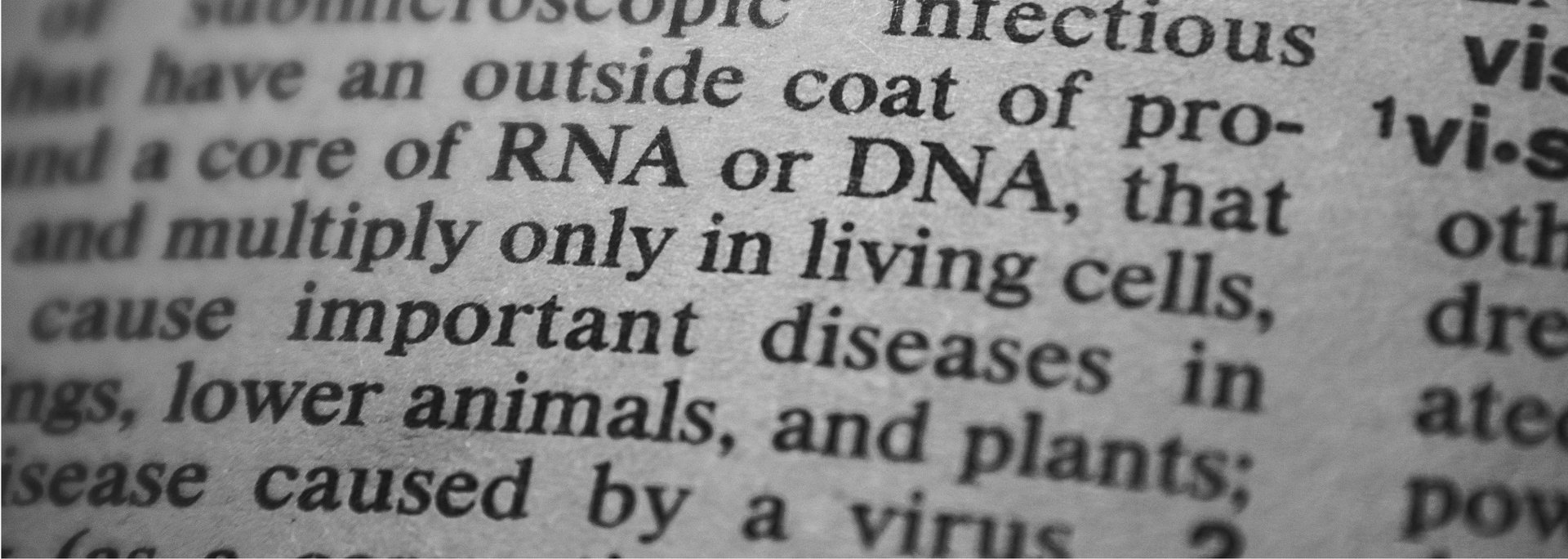

That's not to say that people haven't tried to define it. A little Googling brings up the following:

- Encyclopædia Britannica: 'Any harmful deviation from the normal structural or functional state of an organism, generally associated with certain signs and symptoms and differing in nature from physical injury.'

- Merriam-Webster: 'A condition of the living animal or plant body or of one of its parts that impairs normal functioning and is typically manifested by distinguishing signs and symptoms.'

- MedTerms (archived): 'Illness or sickness often characterised by typical patient problems (symptoms) and physical findings (signs).'

These definitions aren't identical – but the gist is that disease manifests as signs and symptoms and makes the body function abnormally.

This raises questions. For instance, what about diseases that don't present symptoms? About 20% of COVID-19 cases are asymptomatic, meaning the person who carries the disease doesn't feel ill.³ Does this mean COVID-19 is only a disease when its sufferer suffers?

And as for the body functioning abnormally… Well, what does 'normal' mean anyway?

This second question is particularly important because our definitions of 'normal' change over time – and our understanding of disease changes with it.

Take homosexuality. Younger readers may be surprised to learn that homosexuality was only removed from the American Psychiatric Association's official list of mental disorders in 1973. That was a mere 52 years ago, at the time of writing.

There are stigmas associated with disease

Nowadays, most would consider it unthinkable to consider homosexuality a mental disorder. But this points to another key point – there is a stigma associated with disorders and diseases.

Some might argue that defining obesity as a disease invites negative associations. It's not for nought that the World Obesity Federation, while supporting the redefinition of obesity as a disease, states its '[concern] that any moves to redefine obesity should be sensitive to the stigma experienced by people with weight concerns'.

The counterargument is that not defining obesity as a disease comes with stigmas of its own. We tend to think of diseases as things that happen to us. If we don't consider obesity a disease, are we implying that people living with obesity did it to themselves?

Unfortunately, this manner of thinking remains fairly pervasive. Some people still think of obesity as a lifestyle choice – in other words, that people become obese because they choose to overeat.

However, this ignores many potential causes of obesity – both external and internal.

Take one look at supermarket shelves. It's not hard to see that the processed food industry is on the up and up. Fresh ingredients are harder to come by – and so is the time needed to turn these ingredients into healthy meals.

This is just one example of many. The point is that the environments in which we live play a not insubstantial role in making us obese. Experts even have a name for these environments: 'obesogenic' – that which makes us obese.

And then there are internal factors. Like the fact that injury or disability can make it harder to lose weight. And that some people are genetically predisposed to carrying more weight.

Obesity is complex. Words are powerful. Society is stubborn. It's little wonder that organisations and healthcare professionals don't yet agree on a single definition of obesity.

But perhaps that's the problem. Maybe one definition just isn't enough.

Is one definition enough?

Stop press!

As we were writing this article, a landmark report appeared in the The Lancet medical journal. It saw a panel of global obesity experts call for a new definition of obesity.

The report took no prisoners. It began, for instance, by criticising the standard BMI-based measures of obesity, asserting that they "[undermine] medically sound approaches to healthcare and policy".

However, the biggest shake-up came with its proposal of a two-tiered diagnostic framework for obesity.

Under the proposed framework, obesity would be classified as one of two conditions. These are preclinical obesity, which is defined as a health concern, and clinical obesity, which is defined as an illness.

The panel hopes these new definitions will "open the doors to a more accessible and effective management of obesity". Patients with preclinical obesity, who are not yet experiencing ill health as a result of their weight, can be treated using risk mitigation strategies.

However, those with clinical obesity, who are most at risk of developing serious health conditions, can be given priority treatment.

It's interesting to note, however, that even these experts stop short of defining clinical obesity as a disease. In the report, they call it a "condition of illness [that is] akin to the notion of chronic disease in other medical specialities". (Emphasis ours.)

In any case, this report is a big step forward. At SemaPen, we welcome any endeavour to make obesity treatments more accessible to those who need them. Disease or not, obesity is serious – and serious conditions need serious solutions.

SemaPen is a UK-based weight loss injection clinic. As part of Phoenix Health, we have been helping people with obesity lose weight for more than 20 years.

Sources

1. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn03336/

2. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

3. Augusto, D.G. et al. (2023) "A common allele of HLA is associated with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection" Nature, 620 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06331-x

4. https://www.frontier-economics.com/media/hgwd4e4a/the-full-cost-of-obesity-in-the-uk.pdf\

5. Rubino, R. et al. (2025) "Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity" The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00316-4